Our next game, Dave’s Word Game, comes out tomorrow. This is very exciting for several reasons, but for me personally it’s significant as it’s the first thing we’ve done in Growl, my game engine project I’ve been working on, at first sporadically and then pretty seriously, for the last few years.

I started doing this mostly for fun and for my own learning, but I had a couple of other motivations. The first was that our previous game, Feud, was written in Java using libGDX. libGDX is a great library, but, while I’m not a Java hater, it certainly caused us no end of issues around things like code signing and portability to other platforms, particularly iOS. Compound that with my dream of eventually releasing stuff on Switch and it became clear I needed something else.

Around 2019, I did a little bit of open source work on Halley, the game engine used by Chucklefish and largely developed by Rodrigo Braz Monteiro, a fearsomely talented game programmer. Rodrigo was kind and patient enough to answer all my stupid questions and I eventually managed to port the engine to iOS and to Metal, Apple’s graphics library. I had so much fun. I was hooked.

It was at around this time that I started entertaining the idea of making my own engine. The amount of stuff I’d need to learn was intimidating - I had basically zero experience in graphics programming and none whatsoever in fonts, audio, input, UI and all the myriad other things needed to make even the simplest 2D engine function. A few years later, in early 2022, I took my first baby steps.

I’m not going to try and make the argument here that anyone should make their own game engine. If your priority is to actually ship a game, it’s probably the most time-inefficient way possible to make that happen. I’ve seen so many friends fall into the trap of having so much fun making the engine they never get around to making a game in it, and while I actually think this is a pretty nice outcome it’s not what I wanted for myself. However, I can’t think of any other software project I’ve ever done where I have pushed myself so far, learned so much, and spoken to so many interesting and talented people in the process. If you want to have a good time writing code, a game engine might be the best way to do that.

I’m going to write this chronologically, going through the various different things I had to learn about and implement to get this working. The timeline will be a bit strange - I had to finish Feud while I was doing this, and then at a certain point the majority of development was on Dave’s Word Game itself and not the engine. Feel free to follow along in Growl’s commit history, if you dare.

This post is quite long. Here’s a table of contents.

Let’s go.

Jan-Mar 2022: Engine structure, Metal, OpenGL

I decided at the beginning I was going to use C++ 17; my reasons for this were probably laughably vague, being simply “that’s what Halley uses”. In hindsight, there have been a few C++ 20 features I’ve missed out on but largely 17 has been fine. At the time, though, I barely knew C++, and had some stupid idea that I was going to try and write the engine in such a way that someone could use it without knowing all that “hard stuff” like move semantics. I was quickly disabused of this notion by my good pals Pat and Stu, yet more extremely talented programmers with a seemingly inexhaustible supply of patience for Local Idiot Asking Questions. This is one of the prerequisites of writing a game engine.

(Stu’s new game, Substructure, was revealed recently, and you should definitely check if out if you’re a Factorio sicko like he is.)

I knew just about enough about CMake at this point to hurt myself badly with it. I had to do quite a substantial refactor later in the year.

The structure of the engine was heavily inspired by Halley, which uses a plugin based architecture where everything is a type of plugin; system, graphics, audio, network and so on. The API was designed to be very much like libGDX, with an “outside-in” style of architecture where the user is responsible for bringing the executable entry point. I had to bend this a bit for iOS and Android.

I started out building the basic interfaces for the various APIs, which at the beginning looked like this:

SystemAPIis responsible for input, window management if applicable, logging, interfacing with the host OS and doing things like checking for dark mode or running haptics.GraphicsAPIis for all things drawing. Shaders, sprite batches, textures, all that good stuff.AudioAPIis for audio, duh.

I would eventually add NetworkAPI and ScriptingAPI, but that wasn’t til

quite a bit later.

My first System API was for SDL2, and for graphics it was my old friend Metal. The first thing I ever got it to do was create a window and clear the background colour in it. I was extremely proud of this.

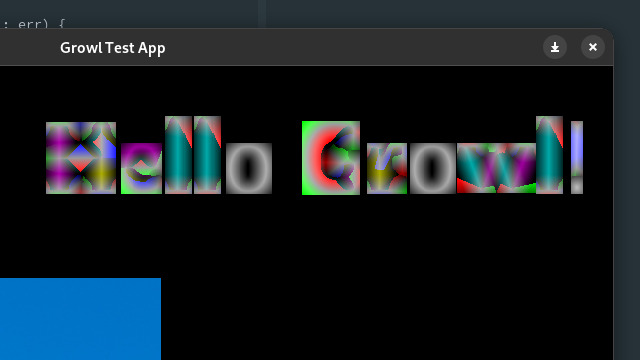

The next thing was loading and rendering textures. Metal makes this relatively easy to do, but I still needed to go and relearn what the hell a projection was, having not touched this kind of maths since university. Here’s an early attempt using some assets from Feud - you can see I hadn’t really got my head around the matrix maths yet.

Eventually I got a somewhat sensible structure working for textures, sprite batches, and shaders. I then started trying to implement the same thing in OpenGL as an additional graphics plugin.

I think I may be somewhat atypical in going from Metal to OpenGL rather than the other way around, and while this did make some things quite hard I think it also taught me some good habits - putting things in buffers, for example, is the default in Metal, and while it’s considered a modern best practice in OpenGL a lot of the beginner tutorials don’t teach it.

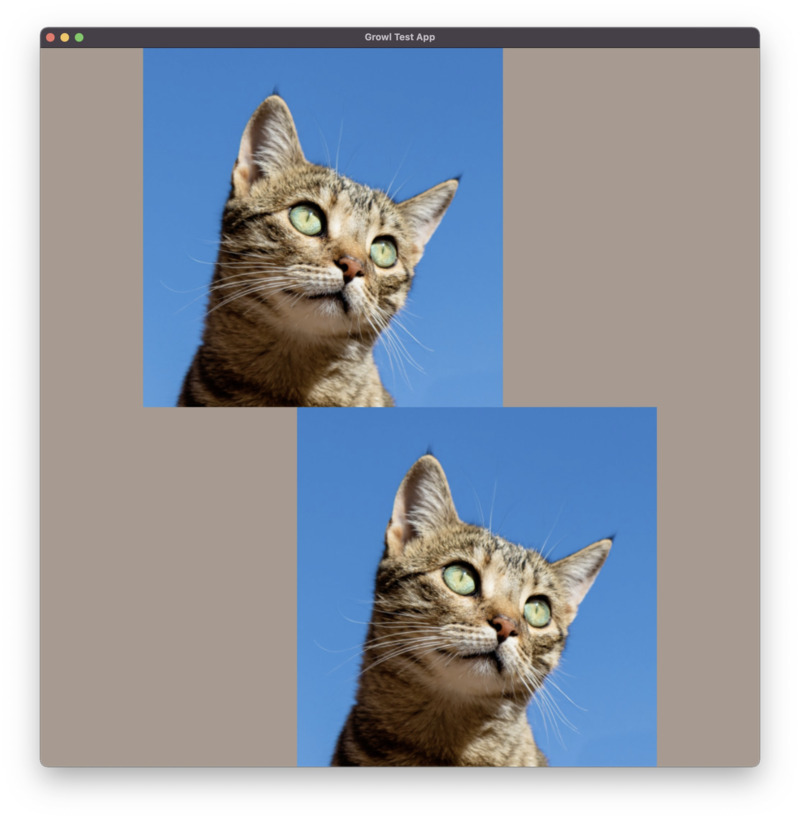

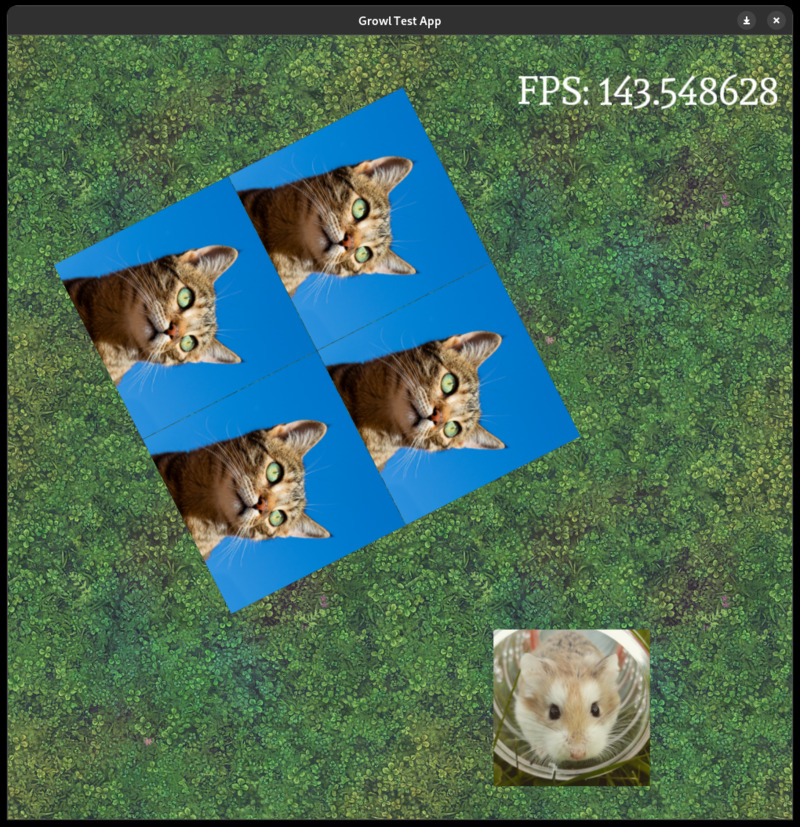

I started using this image of a cat for testing as it was something I could put into a public repo, and it stayed as the unofficial mascot of Growl until I eventually replaced it with a picture of my own cat.

Next, I had my eye on doing texture atlases, something I used extensively in

Feud, and for that I’d need the ability to create those offline. I was and am

resistant to the idea of shipping the engine with an “editor” - I tend to do

everything I possibly can in a terminal and resent ever needing to touch a

mouse - so I made a command-line tool, growl-cmd. I used CLI11 for this, which is great. This tool has

basically been unchanged since; I had a vision of also adding stuff like Metal

shader precompilation to it but never really got around to it.

The texture atlases and render-to-texture came next. This was fun! I learned a lot writing my own bleed algorithm for the texture atlases and implementing the skyline algorithm for the packing, and needing to grapple with concepts like half-pixel correction was a tremendous learning experience even if it did make my brain hot like an old laptop. Some of the test images from the time were trippy, I wish I still had them.

One fairly important thing I added at this point was a Result/Error type. I

don’t really like the way exceptions work in most languages, but I do like Go’s

style of value based error handling, so I made a simple class for this, based on

std::variant. It was at this stage I needed to go and really get my head

around move semantics, rvalues, and a small amount of templates; things I had

little comparable experience in from other languages, so this was hard. The

#joel-learns-things channel on my Discord server got a lot of use this month.

Apr-Jun 2022: Input, fonts and audio

I added keyboard, mouse and gamepad input using SDL’s event system. I remember being surprised at how easy it was - SDL does a huge amount for you here. Having even the most basic input possible suddenly changed this from feeling like a rendering library to feeling like something that could make games. Steady on, kid, long way to go yet.

Because I didn’t at this stage have a particular game I was trying to make, I was free to follow my own interests. I didn’t have any sort of audio support in the engine yet but I had a couple of weeks off work and decided to take a big ol’ detour into text rendering.

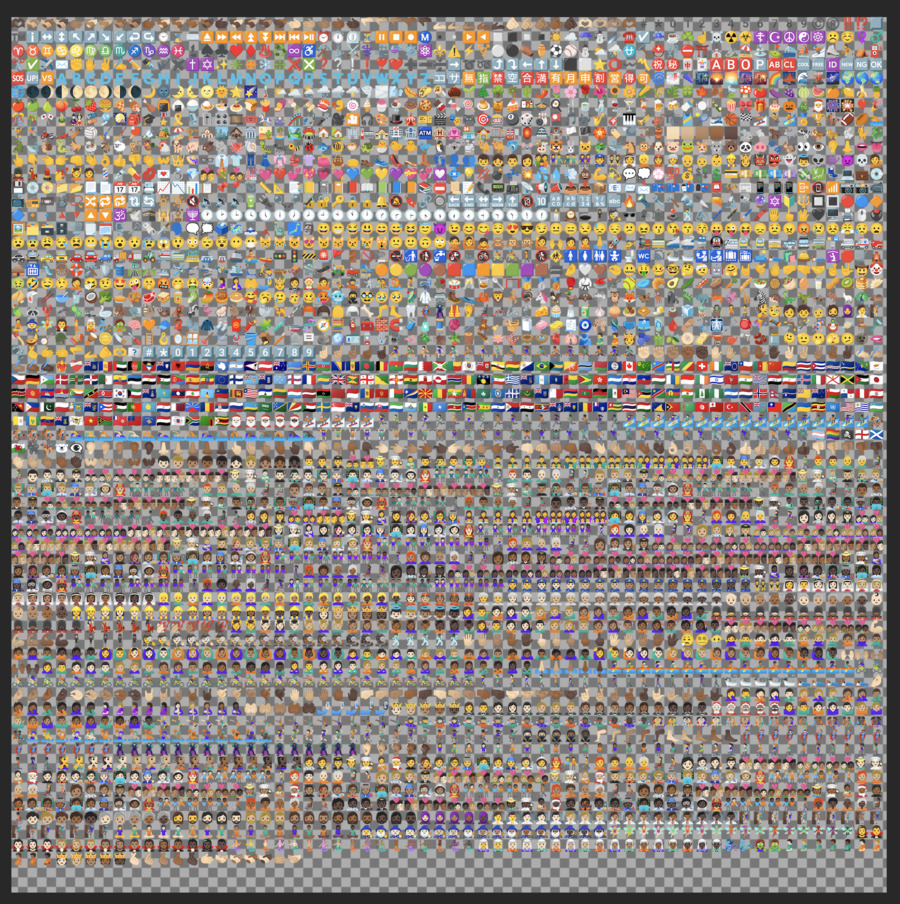

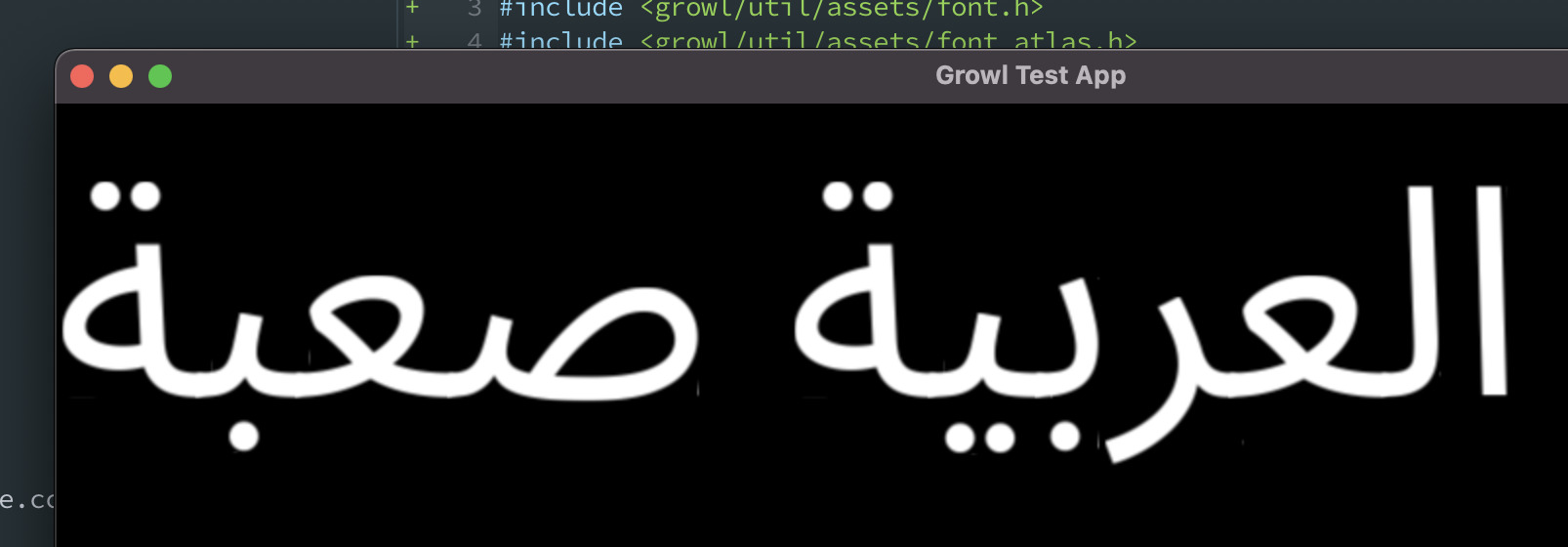

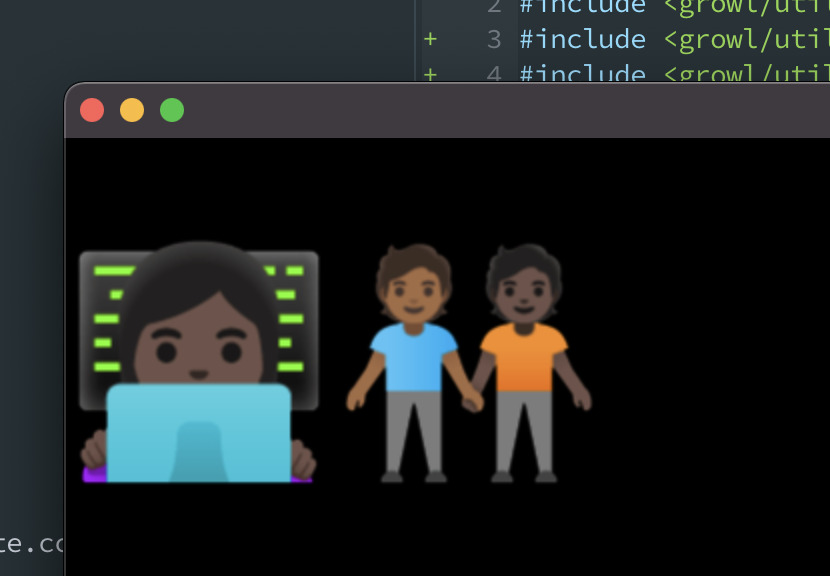

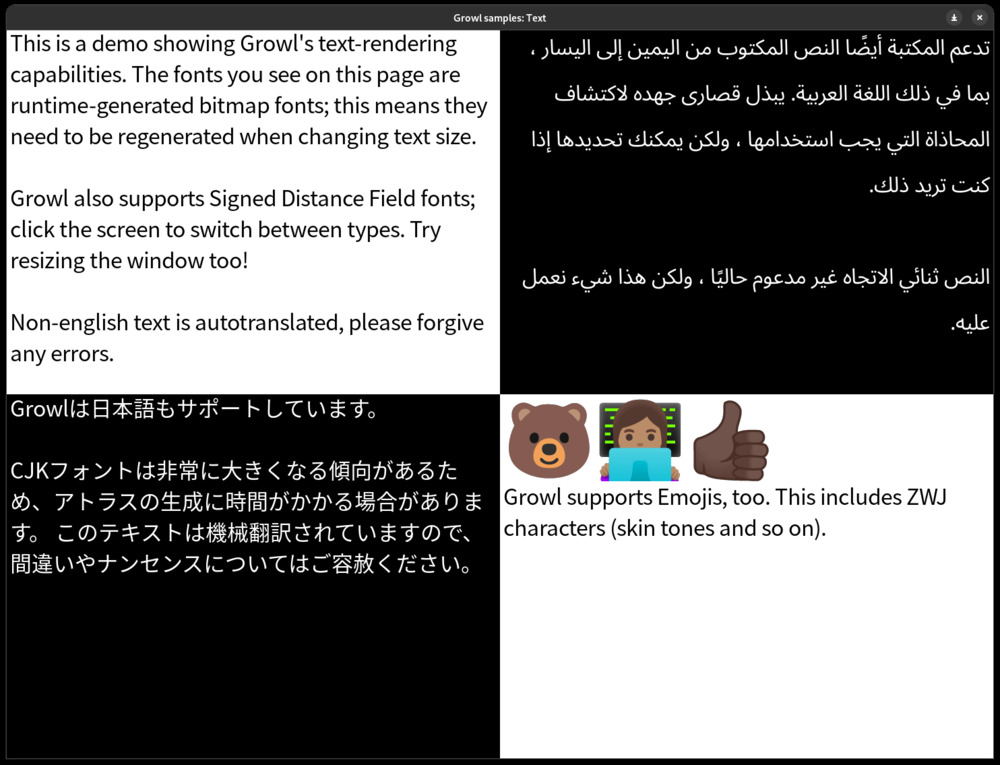

Text is a fascinating topic that more than deserves its own writeup, which I’ve been telling myself I’ll do for three years now. Due to my frustrations getting certain languages supported in Feud, I had pretty big ambitions for this; I was going to support CJK, RTL, BiDi, emojis, the lot. In the end I added Signed Distance Fields to this list. I’m pretty proud of Growl’s text rendering.

The first bit was learning to actually parse fonts and extract the glyphs, so that I could pack them into a texture atlas offline. Feud would rebuild font atlases on the fly, which works totally fine for English and is abysmally slow for Simplified Chinese. Here’s an image showing the extracted glyphs of an emoji font, for some reason:

With font atlases done came rendering the text. I used a combination of Harfbuzz, FreeType and utfcpp to parse strings, determine their layout and then match the glyphs up to those in my font atlas. Harfbuzz does a lot of the work for you, so extending this to support non-Latin scripts and even emojis with Zero Width Joiners (used to specify things like skin tone) wasn’t too much of a stretch.

Next up was the SDF fonts. The big advantage of these is that you can pre-bake just one font atlas at a fixed size, and then use your shader to make that font scale and appear crisp at any other size, within limits. This meant I could do the sort of dynamic text resizing that would have been much harder in Feud, and I wouldn’t have to build fonts at runtime.

I settled on Multi-Channel Signed Distance Fonts for this, a method developed by Viktor Chlumský, inspired by the original Valve paper. This involves generating font atlases using the three colour channels in addition to the alpha channel SDF fonts use.

Integrating this into my rendering stack proved to be quite tricky; I had to do a lot of fiddling with it to get FreeType’s metrics to match up to the metrics emitted by MSDFgen. I’m still making adjustments to it even now, and the MSDF fonts don’t look exactly like their rasterised counterparts, but it’s a difference so slight only I will notice and get annoyed by it. Here are a few old screenshots showing my attempts to get it working.

I implemented line breaking after this, using libunibreak. In the end I didn’t get around to doing bidirectional text, but it’s on my list. Here’s a screenshot showing where the text rendering ended up:

I finally got around to doing audio next. I went with SoLoud, which does most of the work for me, so in the end I didn’t need to learn that much about audio programming. However, SoLoud is now effectively unmaintained, so I have a vague plan to migrate to MiniAudio, which will require me to learn a bit more as that library is rather more low-level.

The one slightly tricky bit with the audio was getting streaming to work from my asset bundle - I don’t encrypt the data in the bundle but it’s all smooshed together contiguously, so I needed to write some file adapter code to get SoLoud to be able to read it.

Jul-Sep 2022: ImGui, iOS and the beginnings of Dave’s Word Game

One thing I regret not investing more in when developing Feud was tooling. Any change to the game, even tweaking an asset or changing the speed of an animation, required the other lads to upload things to Google Drive and then get me to make the change in the code. While I wasn’t interested in building an editor for Growl, I did want some sort of way to make it easier to plug in external tooling.

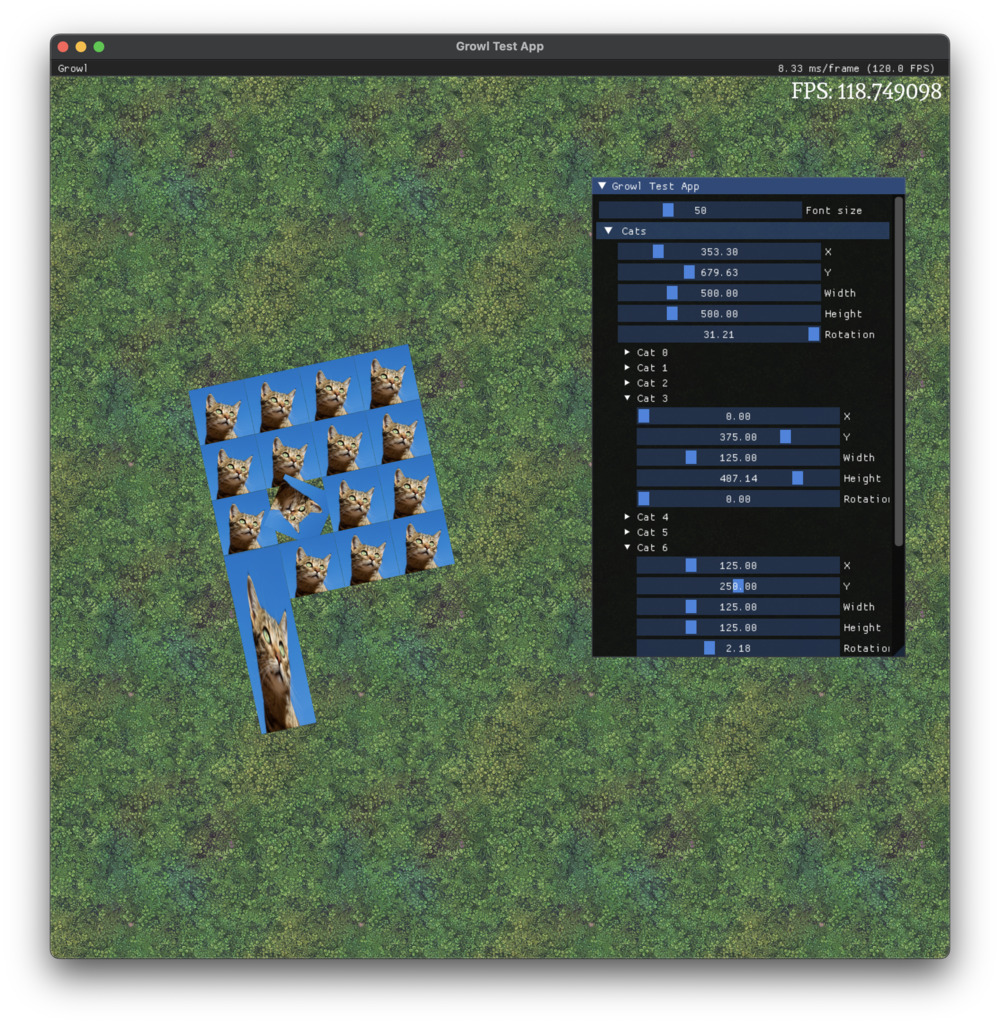

Dear ImGui was the natural choice for this. I added a little debug menu in-game, and then certain variables could be bound to sliders in that UI. I would go on to add quite a bit of tooling to this menu, eventually turning it into something a bit more like an embedded editor, though still much leaner than a real editor would be.

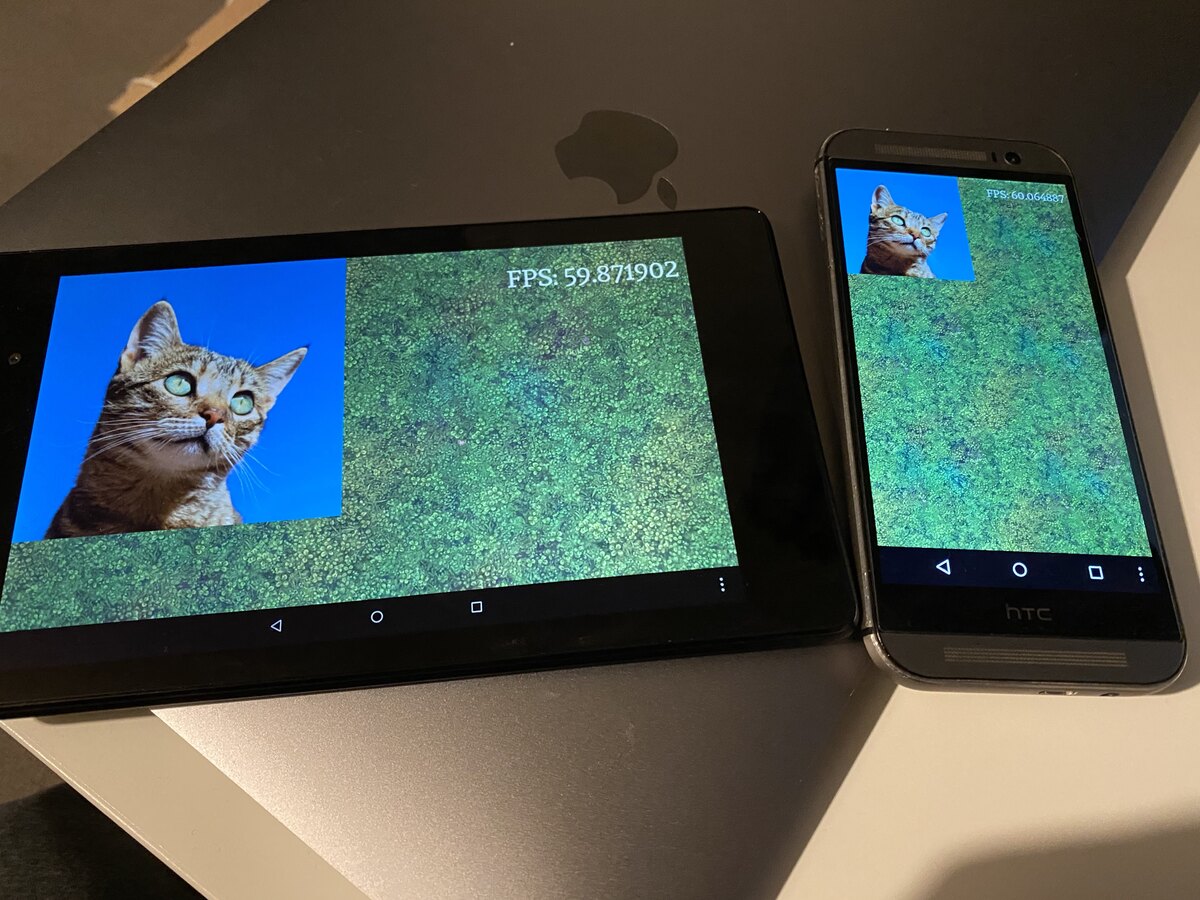

I also started doing the porting process here. iOS was the first port of call, as I was a bit more familiar with it, though in the intervening few years I’d forgotten how strange Objective C’s memory model can be. The plugin architecture lent itself well to porting, and Metal is consistent enough between macOS and iOS that I hardly needed to change anything at all, just adjust some memory alignment issues. I was very pleased when I got the test app running on my iPad; it brought back that thrill from the Halley days. Porting is so much fun.

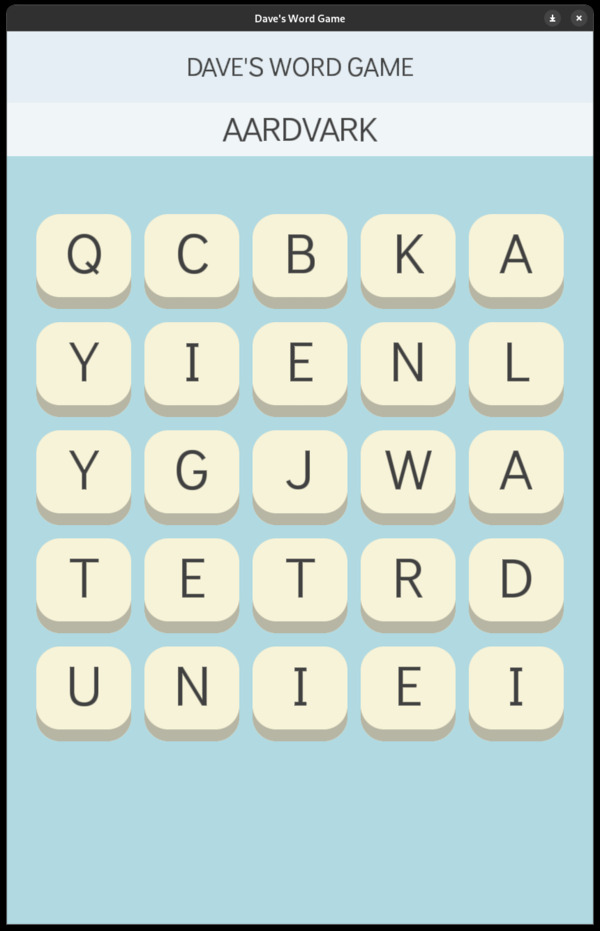

It was around this time that Dave, knowing I was after some kind of simple game idea to dogfood the engine with, told me about his word game idea, then unnamed. From this point on DWG became the guiding force of the engine - I’d work on it for a little bit, realise some other huge thing was totally missing, then go and implement that into Growl. Having this structure meant I was much less likely to go off on a side quest (though that certainly did still happen). Here’s the earliest screenshot I can find of Dave’s Word Game with its original art style, rendered in Growl.

Oct-Dec 2022: Android, silly porting, and scene graph

Android was the next target. I’d done quite a lot of Android development - it was probably the first thing I ever really programmed for - but I’d never gone near the NDK. I ended up using GameActivity, which makes a few things like input handling a little easier.

I found Android really interesting. There were a few issues I needed to iron out - in particular, I only supported OpenGL, not OpenGL ES, so I needed to do a bit of messing with loaders and so on - but for the most part it was relatively smooth. The documentation is decent, and I remain pretty amazed at Android’s commitment to backward compatibility; both my test devices were from 2013 and they worked totally fine.

Amusingly, I could also run it on the Oculus Quest, it being essentially an Android phone strapped to the face.

I was determined to do everything I could to stay in the NDK and avoid having any Java code or build system at all; I really didn’t want to have to mix CMake and Gradle, and having multiple languages felt icky. I wrote a blog post at the time explaining how to package an APK without using any of the Gradle based tools. Later, I would abandon this, as some things simply can’t be done without bridging to Java via JNI.

I would later come to encounter a lot of Android-specific issues, particularly around streaming audio from disk, but at this point I was high on the joy of porting and I was happy.

Things got a little silly from here out.

I had been very deliberately architecting the engine towards maximum portability, and getting it to run on 3DS (via the homebrew SDK) felt like the best possible test of that. It worked, kind of! I never got around to doing audio, but it was able to load stuff from the asset bundle and render it on screen.

3DS is a tricky platform for Growl, which is built around the assumption that whatever it’s running on has a shader pipeline of some description. The 3DS has programmable vertex shaders but, weirdly, fixed-function fragment shaders. This meant that getting stuff like the SDF font rendering to work was a little beyond my capabilities. Still, a good learning experience, and I actually made a small contribution to Harfbuzz to get it building on arm-none-eabi; getting to interact briefly with Behdad Esfahbod left me a little starstruck.

I also got the engine running on web, via Emscripten - because Emscripten ships with an SDL2 implementation this ended up being very easy indeed. You can have a play with it here, though bear in mind it’s a very old version of the engine!

Back to DWG, and realised the next thing I needed was a scene graph or some sort of UI toolkit; I found that I was essentially implementing that in the game and thought it made more sense to have in the engine. I put together a simple hierarchical scene graph, where positions, scales and rotations could be put on a parent node and they’d be applied to any children. I had to root around in my brain to remember how order of operation for this type of matrix maths works, but it wasn’t too complicated.

2023: I did other things

I took a break from Growl at the start of 2023, and this ended up being a break that lasted nearly the whole year. This surprises me, looking back! I don’t remember a period where I wasn’t working on it. Time is an illusion and all that.

Anyway, in 2023 I had a couple of other projects consuming all my time. I had to get Feud out of Early Access, and there was quite a lot to do there. One of the tasks was to get it built for the Epic Games Store, and making it work with Epic Online Services. EOS don’t ship a Java SDK, and Feud is written in Java, so I ended up being inspired by steamworks4j and made my own library, eos4j. This was my first experience using JNI, and it would come to be very useful later down the line when I had to move a bunch of Growl’s Android stuff out to Java.

You should play Feud, by the way. It consumed eight years of my life and I have a sort of resentment towards it but I’m also really proud of it.

Towards the end of 2023 I dipped my toes back into Growl, hooking up the ImGui debug menu to the scene graph. This meant I could have various widgets and doodads attached to the nodes in the graph, making it organised a bit more like what you’d see in the editor of a big game engine.

In the new year, I got a bit distracted again.

Jan-Jul 2024: Scripting and shaders

I had this idea that having built-in scripting support would be really useful in some games. I had a little toy shmup idea I was playing around with and being able to adjust enemy behaviour and so on without needing to rebuild the game sounded really cool. We ended up not using this at all in DWG, but it’s in the engine, it works, and I spent ages on it so I’m going to talk about it.

Rather than pick one language as the default, I wanted to make scripting languages act like plugins via a Scripting API. The idea was you could bind functions to scripts and then the scripting layer in the engine would take care of doing all the language-specific bits to connect everything up. I would provide Lua scripting as a reference implementation, but wanted it to be possible to drop in something like Wren.

This is insanely over-engineered, and it took about six months of my life to get it properly working. In the process I had to take my first hesitant steps into the world of template metaprogramming, from which I have still not psychologically recovered.

The end result is this fairly clean setup where you can attach a script like this to any arbitrary node and “override” any methods that have been made available to the scripting layer.

local node = {}

function node:setX(x)

Node.setX(self, x * 2)

end

return node

I’ve not revisited the scripting stuff in over a year and still haven’t really used it in anger, so no doubt there’s still a lot to do there.

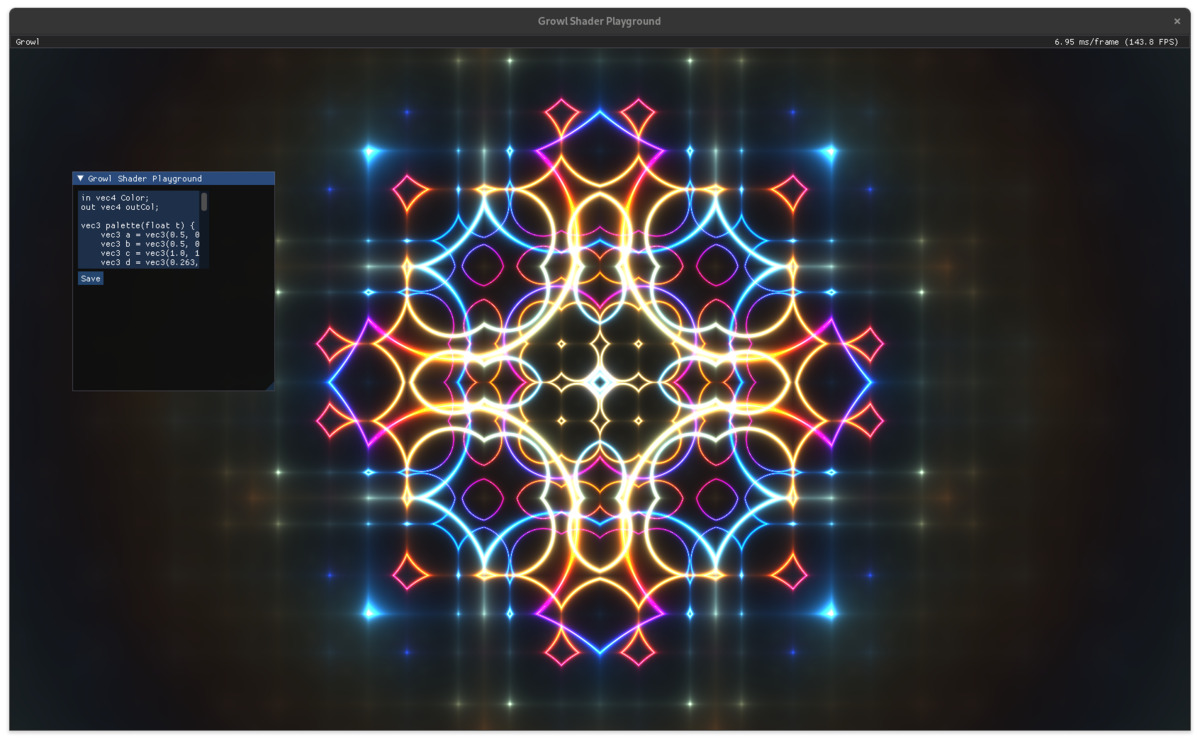

Towards the middle of the year I also put a bit of time into tidying up how Growl manages shaders, applies uniforms and allows for users to package custom shaders in the asset bundle, then edit them live in the debug menu. Once again, this wasn’t something I needed for DWG, but I’d been playing around with Shadertoy and thought it’d be neat to have a little shader playground in Growl.

I went with a setup where every shader gets a shared “header” prepended to it before compilation, so that every (fragment) shader has access to variables like time and screen resolution. I made my little playground and started using it when doing shader tutorials. It’s on GitHub.

Aug-Dec 2024: UI and starting DWG in earnest

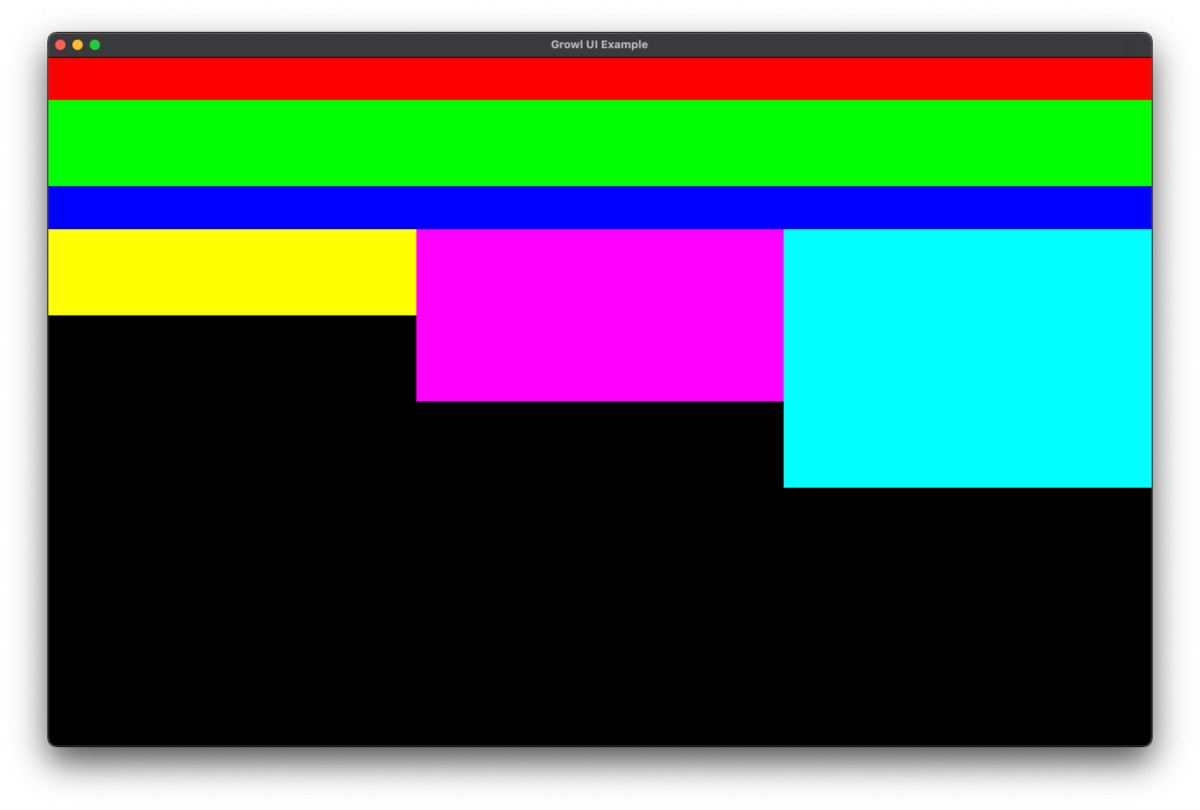

I had a scene graph, now I needed to add the UI framework on top of that. I decided to go with something fairly similar to GTK, the first UI library I ever used - widgets (a specialisation of the scene graph’s nodes) get added as children and provide their packing preferences (expand, fill, margins and so on).

I followed Scene2d’s approach to validation/invalidation/layout, which worked nicely at first and then became quite tricky due to text reflow causing invalidations up and down the tree. I had to tinker with that for quite a while to get it working reliably.

Towards the end of the year, once the UI stuff was in, I felt it was time to go back to DWG armed with the new Growl features and Dave’s newest designs. We built a prototype relatively quickly, and had our families playing with it over the Christmas holidays.

DWG had always been intended as a small dogfooding exercise, but once we started playing it and saw our families interact with it we realised it was actually really fun, and after some encouragement we decided to try and make the whole thing.

2025: Haptics, networking, misc.

The focus now squarely on DWG, everything I did on Growl was driven by whatever that game needed at the time. This meant the development was quite scattered, mostly small additions and changes rather than big new features, though I did add a couple of significant things.

One really fun addition was haptic feedback - in Growl this is responsible for both mobile haptics and controller rumble. Building this out was really enjoyable, and the addition of haptics into the game made it immediately feel so much more polished. iOS in particular has a really robust and powerful haptics system that you can do a lot with. It’s hard to show it in a screenshot, though.

The other big addition was networking support. This was a lot harder than I expected; networking is one area I have a lot of confidence in, but the difficulty ended up being around managing dependencies for it. The various different platforms handle networking and particularly TLS in quite different ways, with some having libraries provided and some requiring you to bring your own. I use vendored dependencies in Growl, but OpenSSL is so large that adding it immediately ballooned the size of the build. It took a while to work out which libraries to use on which platform.

The rest of the year was spent adding what I needed, when I needed it: dark mode querying, text input, new UI widgets, file I/O, interpolations, a preferences system and mobile share sheets all made appearances. Most of my time was spent in the DWG codebase itself, though, so Growl changes became a bit more sporadic.

I implemented things like platform login and achievements in DWG rather than in Growl. I don’t really have a super good justification for why this stuff felt like it didn’t belong in the engine. Some of the flows do end up being quite game-specific, and it’s quite hard to make achievements stuff generic, but I might well move it in or make it a separate library at some point.

Tomorrow, December 15th, Dave’s Word Game launches on iOS and Android. We plan to put the PC version out a little later. Please play it! You can preregister at playdwg.com.

Conclusions, acknowledgements, and what’s next

In the grand scheme of games and game engines, Growl is very basic. It’s 2D only and doesn’t have many of the more advanced features of an engine like Unity or Godot. If the goal was simply to build Dave’s Word Game, it probably would have been faster to just do it in Java again.

But! If I hadn’t started making my own engine, DWG would probably not have happened. I wouldn’t have learned C++, or OpenGL, or Metal, or about font rendering, or how to integrate Lua, or CMake, or the myriad other little bits of knowledge that are now lodged in my brain. It has been intensely rewarding, and probably the most enjoyable project I’ve ever undertaken.

I’ve also met some really interesting and inspiring people. In particular are the denizens of the Game Engine Developers Discord server, which I was added to at a time when I couldn’t reasonably call myself that. They have been incredibly supportive, and I want to shout out Ruby, Rodrigo and Pat in particular for answering my stupid questions, giving encouragement, and saying “hell yeah” at exactly the right moments. Also Ruby for the phrase “solve problems that exist” which, yeah, I’ll keep trying.

It’s hard to say right now what the next things to add to Growl are. We have a roadmap for DWG, but it’s mostly things that won’t need additions to the engine. Inevitably, some of them will turn out to need changes, but I can’t yet foresee any big new features. Perhaps whatever the next game is will drive those requirements!

At the back of my mind I do have the desire to tidy up Growl, document it, make it usable to other people. That’s a lot of work, though, and it’s not yet clear there’s anyone out there who wants to use it who wouldn’t be better served by something like Godot, so I’m holding fire.

If you’re thinking about building a game engine, be aware that it will consume so much more of your life than you expect. But you’ll have the best time.